How GOP-backed voting measures could create hurdles for tens of millions of voters

By Amy Gardner, Kate Rabinowitz and Harry Stevens

March 11,2021

The GOP’s national push to enact hundreds of new election restrictions could strain every available method of voting for tens of millions of Americans, potentially amounting to the most sweeping contraction of ballot access in the United States since the end of Reconstruction, when Southern states curtailed the voting rights of formerly enslaved Black men, a Washington Post analysis has found.

In 43 states across the country, Republican lawmakers have proposed at least 250 laws that would limit mail, early in-person and Election Day voting with such constraints as stricter ID requirements, limited hours or narrower eligibility to vote absentee, according to data compiled as of Feb. 19 by the nonpartisan Brennan Center for Justice. Even more proposals have been introduced since then.

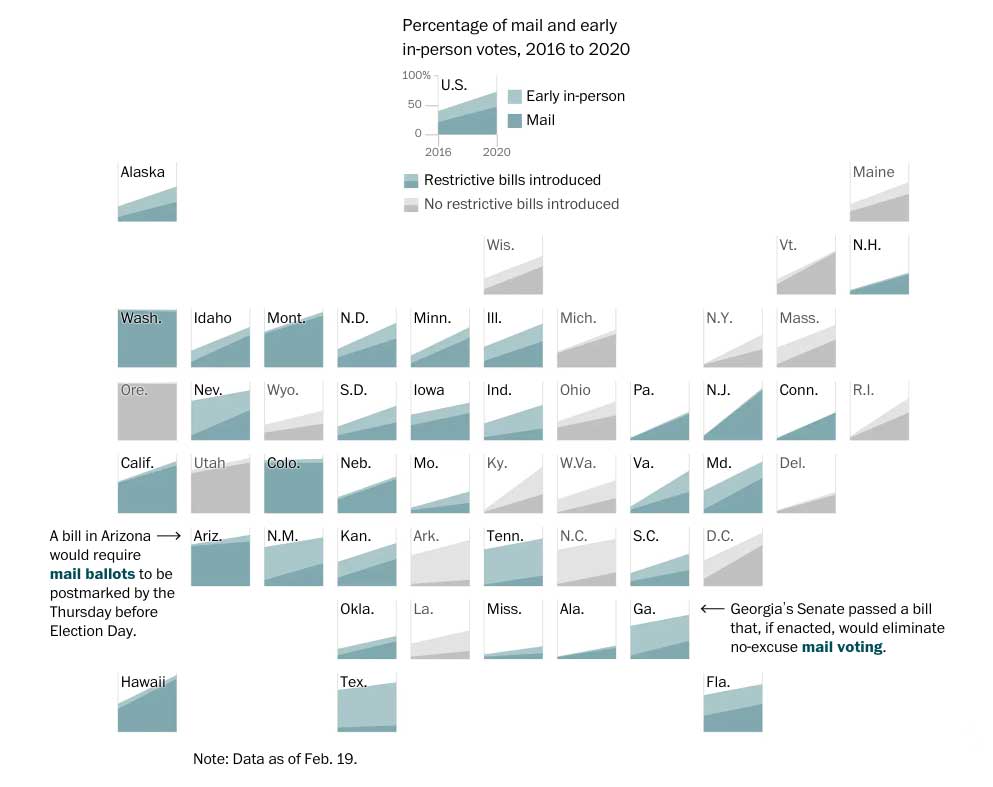

Restrictions to mail and early voting proposed in 33 states following a spike in 2020

Proponents say the provisions are necessary to shore up public confidence in the integrity of elections after the 2020 presidential contest, when then-President Donald Trump’s unsubstantiated claims of election fraud convinced millions of his supporters that the results were rigged against him.

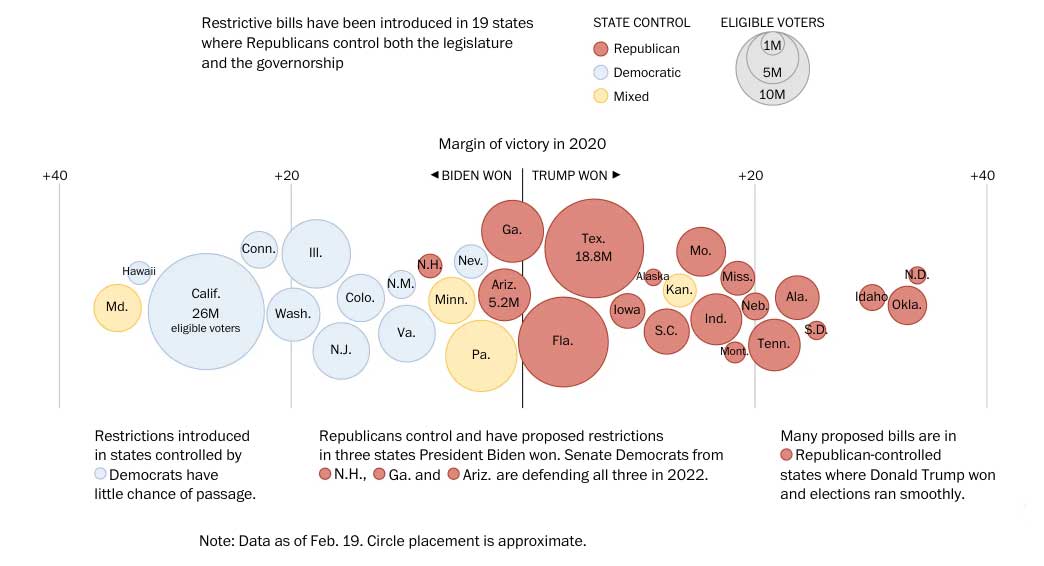

But in most cases, Republicans are proposing solutions in states where elections ran smoothly, including in many with results that Trump and his allies did not contest or allege to be tainted by fraud. The measures are likely to disproportionately affect those in cities and Black voters in particular, who overwhelmingly vote Democratic — laying bare, critics say, the GOP’s true intent: gaining electoral advantage.

The rush to crack down on voting methods comes after many states temporarily expanded mail and early voting in 2020 because of the coronavirus pandemic, leading to the largest voter turnout in more than a century. The changes reshaped both who turned out and how they voted, with an astounding 116 million people — 73 percent of the electorate — casting their ballots before Election Day, according to The Post’s analysis.

In many states, Democrats are trying to make those expansions permanent — and broaden voting access in other ways. Congressional Democrats are also pushing a sweeping proposal to impose national standards that would override much of what Republican state lawmakers are trying to constrict, including measures that would provide universal eligibility to vote by mail, at least 15 days of early voting, mandatory online voter registration and the restoration of voting rights for released felons. The measure has passed the House but faces steep opposition in the evenly divided Senate.

Republican state legislators, meanwhile, echoing Trump’s false claims that the election was stolen from him, are pushing hard in the other direction.

The outcome of dueling efforts will vary depending on partisan control of statehouses. The same party controls both legislative chambers and the governorship in 38 states — 23 of them Republican and 15 of them Democratic. Many of the most restrictive proposals have surfaced in states where the GOP has a total hold on power, including Arizona, Georgia, South Carolina, Missouri and Florida.

Millions of voters could face new limits to mail and early in-person voting

Some of the bills in Democratic-controlled states such as Washington, one of the first states to implement all-mail voting, have little chance of passage. But others are steaming ahead: In Georgia, for example, the House has passed a sweeping bill that would limit early-voting hours on weekends and restrict the use of drop boxes for mail ballots, among other provisions. The state Senate, meanwhile, approved a measure that would eliminate no-excuses absentee voting altogether — limiting eligibility to those ages 65 and over, people with disabilities or those who will be away from home on Election Day.

Limits to early or absentee voting are the most common measures among this year’s batch of proposed restrictions, with such bills on the table in 33 states. Nearly 85 million voters used one of those methods to cast their ballots in those states last year — more than half of all Americans who voted in the Nov. 3 election.

And the new proposals could do more than rein in early and mail voting. Like squeezing a balloon, the measures could dramatically shift voting to Election Day. That has raised alarm among voting rights advocates that the 2022 midterm elections and 2024 presidential contest could be marred by catastrophically long waits to vote — particularly in big cities, where lines are already a common hurdle for millions of Americans.

“Long lines are going to be the story of 2022 unless something is done,” said Democratic elections lawyer Marc Elias, who said he is preparing for a “busy year” of litigation if these laws are enacted. “We have to recognize early on in this next election cycle that this is now the defining feature of the Republican Party, in competitive states and uncompetitive states. In red states and blue states. They don’t run on economic issues, or even social issues. They run on shrinking the vote.”

Republicans deny the bills are aimed at suppressing turnout, saying they are essential to improving public confidence in the integrity of elections, even in places where elections ran smoothly, such as Florida.

“There’s nothing wrong with securing a great system,” said Florida state Sen. Dennis Baxley at a committee hearing Wednesday in Tallahassee, where lawmakers gave initial approval to a proposal to curtail the use of ballot boxes and eliminate automatic registration for absentee voting, which would force voters to reapply each election cycle.

Other Republicans noted that some of their proposals will help speed the process. The Florida bill, for instance, would allow election officials to begin mail-ballot tabulation earlier in the election cycle — a provision state elections supervisors support because it will ensure a quicker result and fewer doubts about the outcome.

In a statement, Mandi Merritt, a spokeswoman for the Republican National Committee, said that the national party “remains laser focused on protecting election integrity, and that includes aggressively engaging at the state level on voting laws and litigating as necessary.”

“Democrats have abandoned any pretense that they still care about election issues such as voter roll maintenance and restricting ballot harvesting that were once welcomed as reasonable and routine,” she added. “The reality is that we want all eligible voters to be able to vote and vote easily — but voters must also have confidence that our elections systems have safeguards to prevent fraud and ensure accuracy.”

Nevertheless, multiple scholars and historians said the proposed restrictions would amount to the most dramatic curtailment of ballot access since the late-19th century, when Southern states effectively reversed the 15th Amendment’s prohibition on denying the vote based on race by enacting poll taxes, literacy tests and other restrictions that disenfranchised virtually all Black men.

It took many more decades for Congress to prohibit such laws and broadly enshrine voting rights with the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and other anti-discrimination laws. Voting rights advocates say the avalanche of proposed restrictions flowing through state legislatures this year could undo much of that progress.

“There’s this risk that we’re witnessing the rollback of the ‘Second Reconstruction,’ ” said Edward B. Foley, a law professor at Ohio State University, using a common term for the civil rights era. “It’s not exactly the same as the end of the first Reconstruction, and one has to hope that it won’t be. But there are enough parallels to be nerve-racking.”

Hunter Tomlinson delivers his ballot at a drop box in Weber County, Utah, on Oct. 23. (Kim Raff for The Washington Post)

Targeting mail voting

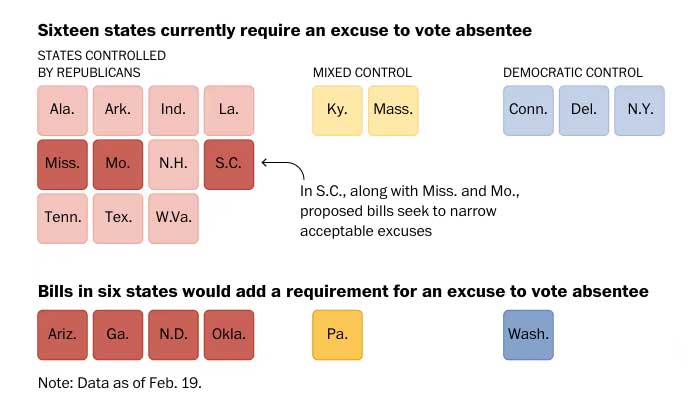

Of the roughly 250 voting restrictions proposed in 43 states — seven times the number introduced in state legislatures by the same time last year — about half seek to limit mail voting, according to the Brennan Center. Proposals target every step of the process, including limiting who is allowed to cast ballots by mail, eliminating the option of being sent a ballot automatically each election cycle and adding ID, notary or witness requirements.

Far more Democrats than Republicans voted by mail last year, in part because Trump warned his supporters to steer clear of mail ballots, falsely asserting that the process was not secure, and in part because Democrats urged their own to take advantage of the option to avoid long lines on Election Day. As a result, many of the proposed curtailments on mail balloting are expected to make it harder for Democrats to vote than Republicans.

Arizona, Georgia and Pennsylvania are among the nine states considering limiting mail voting — or further limiting it — to narrow groups of people, such as seniors or those with disabilities.

Trump contested the results in all three states last fall, claiming falsely that lax security and new rules imposed illegally by judges caused his defeat there. With electoral margins of approximately 10,000, 12,000 and 82,000, respectively, these states could easily have swung for Trump if some of the proposed restrictions were in place last year, experts say.

One extraordinary proposal in Arizona would require mail ballots to be postmarked by the Thursday before Election Day, even if they arrive at election offices before polls close.

No evidence has surfaced to support Republican claims of widespread fraud in the state, where President Biden defeated Trump by less than 11,000 votes, and where most Arizonans have been voting by mail for more than a decade. The Republican governor, Doug Ducey, told Trump in the Oval Office last year that it is “difficult, if not impossible, to cheat” under the state’s mail-voting system.

Trump was open about his view that expanding mail voting would benefit Democrats, but he wrapped his grievance in a false narrative of fraud that conjured unsubstantiated beliefs among his supporters that thousands and even millions of absentee ballots were fraudulently submitted. He also falsely claimed that there was no security in place to prevent ballot theft, and that election workers had abetted a giant crime by not checking signatures on ballot envelopes; sending ballots to the deceased or to empty lots; double- and even triple-counting Democratic votes; or accepting van loads of forged ballots at counting facilities.

No evidence has emerged to substantiate any of those claims.

But Trump’s attacks on voting through the mail led many Republicans to shy away from using mail ballots, and they opted instead to vote in person on Election Day.

In Pennsylvania, Biden won 76 percent of the absentee vote, while Trump won 65 percent of the Election Day vote. In Georgia, Biden won 65 percent of the absentee vote, while Trump won 60 percent of the Election Day vote.

Michael McDonald, a political scientist at the University of Florida, noted that the main reason Trump’s supporters don’t believe U.S. elections are secure is because Trump and his allies have drummed that point into them. Their claim of wanting to improve perceptions of voter integrity, he said, is an excuse to enact suppressive legislation that would disproportionately affect Democrats.

“If Republicans truly wanted to increase confidence in elections, they would stop saying, ‘Don’t trust the elections,’ ” McDonald said.

Georgia voters stand in line at a Gwinnett County polling place on Jan. 5 to cast ballots in two U.S. Senate runoffs. (Melina Mara/The Washington Post)

Election Day pressure

Some of the GOP proposals would strain the overall election system — particularly in states with a history of disenfranchising voters of color, who often experience long lines in their precincts, among other hurdles.

In Georgia, for instance, Democrats say the Republican proposal to curtail early voting on weekends is a direct broadside at “Souls to the Polls,” the get-out-the-vote program that encourages Black voters to cast their ballots after church on Sundays during early voting.

Fewer early-voting hours would transfer more pressure onto Election Day resources. The same is true for another proposal that would prohibit election officials from accepting grants from nongovernmental entities. Such philanthropic grants are widely credited with helping election officials prepare for the surge of mail balloting and set up safe in-person voting amid the pandemic.

“There is no justification for that. None,” said Georgia state Sen. Elena Parent, a Democrat from the Atlanta area. “All it will do is lead to longer lines.” As for the Republican rationale that limiting early-voting hours is an equity issue for smaller counties with fewer resources, Parent said: “It’s not an equity issue when one county has a million people and others don’t. The equity issue is preventing the very populous counties from making voting accessible for their people.”

Georgia Republicans have also proposed banning “line-warming” activities such as passing out water and blankets to voters standing in long lines. Supporters of the measure, including Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger (R), say the practice encourages illegal campaign activity if volunteers are advocating for their preferred candidate and handing out free goodies in the process. Opponents say such activities are necessary to ease the discomfort that many voters face in cities that regularly struggle with long lines.

[The most extreme voting restrictions proposed by the GOP]

As one epicenter for the voting wars this year, Georgia’s debate over election restrictions has prompted impassioned speeches from Black lawmakers and civil rights leaders about the echoes of racist voter suppression they see in the Republican proposals.

“Today is a dark, dark day in our state,” Rep. Nikema Williams, the chairwoman of the state Democratic Party, said on March 1, the day the House approved its elections bill. “Republicans voted as a caucus to enact the most blatantly racist attacks on voting rights in the South since Jim Crow, after losing an election they planned, built and oversaw.”

Georgia state Rep. Barry Fleming, the top Republican booster for the sweeping House election bill, said during debate over the measure that day that the proposed law would “begin an effort to restore confidence in our election system by the voters of the state of Georgia.” Fleming did not respond to a request for an interview.

In Alabama, a proposal is under consideration to eliminate straight-ticket voting, which critics said is yet another example of a measure that would create longer lines. In Tennessee, Republican state Sen. Janice Bowling proposed eliminating early voting entirely — but withdrew the bill when she found no one to take it up in the House.

Bowling explained her rationale for the measure to the Herald Chronicle of Winchester, Tenn.: “There was a time in the not-too-distant past where we didn’t have early votes,” she said. “People went to their precinct on Election Day and they cast their ballot, which is one of the most important things citizens can do.”

Tennessee is among the states considering stiff new restrictions even though it is a deeply red state where no one contested the results last year. Another is Iowa, where Gov. Kim Reynolds (R) this week signed legislation that reduces early- and Election Day voting hours and moves up the deadline for mail ballots to arrive at local election offices.

Election worker Kikumi Smith sorts absentee ballots in Marquette, Mich., on Oct. 20. (Salwan Georges/The Washington Post)

Such red-state initiatives also suggest that many Republicans feel compelled to propose restrictions to signal their loyalty to Trump and his supporters — and to avoid a primary challenge in their next elections.

“No one questioned the legitimacy of anything that happened in our state election,” said Sharon Steckman, a Democratic state representative in Iowa and a leading critic of the Republican election bill. “They won. They won overwhelmingly. We had no fraud in Iowa.”

Steckman thinks the restrictions could hurt Republican voters, too, especially with so many first-time voters coming out to support Trump last year.

“We have a lot of rural Iowa that went solidly for Trump,” she said. “We lost a Democratic seat we had for 40 years. I’m not sure how it’s going to play out, but there were a lot of people we had never seen before at the polls — young men, most of them. Young, White men.”

Iowa Republicans defended the new measures. David Kochel, a longtime GOP strategist in the state, said a provision that would prevent local election administrators from unilaterally changing their counties’ voting rules is reasonable.

“Auditors took advantage of the pandemic to do things outside their statutory authority,” Kochel said. “This just makes sure every voter in every county has the exact same access as the person in the neighboring county or neighboring town.”

Kochel also said curtailments of early voting and Election Day voting are unlikely to produce long lines in his state, where waits are rare.

A building battle

The Republican-backed bills are causing some angst inside the party, as some worry that support for the measures could hurt lawmakers in competitive districts. One GOP strategist in Georgia, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to describe internal party strategy, said state Republican leaders gave lawmakers “the green light to drop whatever bill they wanted” to placate Trump loyalists and avoid a primary challenge.

The plan was to prevent most of the measures from actually reaching the House and Senate floor, the strategist said. But now both the Georgia House and Senate have passed substantive bills.

That is forcing Republican lawmakers from more competitive districts to choose their poison: risk a primary challenge by voting against the measures, or risk a general-election challenge if they support them.

Voters line up outside the John F. Kennedy Library in Hialeah, Fla., on Nov. 3. (Michael Robinson Chavez/The Washington Post)

If many of the measures proposed across the country pass, legal scholars and voting advocates alike say some will be difficult to defend in court. Foley, the law professor at Ohio State, said taking away a previously granted voting right will prompt scrutiny of the law’s rationale — with the burden on the government to justify a new hurdle for voters.

Democrats will also be armed with the fact that until Trump launched his campaign against mail voting, Republicans were champions of the practice, passing legislation in Florida, Pennsylvania and elsewhere, and developing sophisticated ballot “chase” operations to encourage their voters to request, fill out and return mail ballots.

Arguing that some of the proposals could disproportionately affect people of color is a trickier legal prospect because of the federal bench’s history of narrowly defining racist intent under the Voting Rights Act.

Laws that return states to pre-coronavirus standards will also be harder to challenge given the extraordinary circumstances that prompted voting changes in 2020.

But there is little question that a new wave of election-related litigation will follow quickly if any of these measures are enacted.

“We are actively monitoring every state’s legislature to see whether they are going to enact suppressive voting legislation,” said Elias, the Democratic lawyer. “I can promise those Republican legislatures that if they violate the rights of their voters in an effort to curry favor with a failed one-term president, we will see them in court.”

Absentee and overseas ballots are processed in Atlanta on Nov. 3. (Melina Mara/The Washington Post)